On October 15, Bartlett High School in Anchorage, Alaska, held an earthquake drill for the Great ShakeOut, a global earthquake preparedness day. During the drill, office staff had to try to explain to a parent who didn’t speak English that everyone should drop to the floor, crawl under a solid surface and hang on to that surface. He didn’t understand. They tried to tell him to hold on to the office doorframe. He still didn’t understand: he left then returned. The earthquake drill was only a minute long, and the office staff spent the whole time trying to get him to understand how to participate, said Lisa Prince, an assistant principal over freshmen who coordinated the drill.

Disaster practice like the Great ShakeOut can teach participants what to do and show holes in their preparations. Here are five things ShakeOut participants from all over the country learned.

Know the hazards where you live: University of Missouri, Columbia, Mo.

Almost one in three University of Missouri freshmen in 2011 came from outside the state. That means they may not have heard of the New Madrid fault zone, the most active fault zone east of the Rockies.

Eric Evans, the university’s emergency management coordinator, wants to educate students about it.

With good reason. An earthquake in New Madrid, Mo. on February 11, 1812, caused tremors in Boston and reportedly caused the Mississippi River to flow backwards,

according to nationalgeographic.com. Even though the university is about 275 miles away, it’s extremely vulnerable to damage from an earthquake in the New Madrid seismic zone, because of its proximity to the Missouri River, Evans said.

[caption id="attachment_19291" align="alignright" width="300"]

Photo courtesy of Eric Evans, Emergency Management Coordinator for the University of Missouri[/caption]

For the university’s Great ShakeOut event, the emergency management office set up maps showing earthquake-prone areas. Students from the Geology Department explained the earthquake risk. Evans said many students were amazed to learn how common earthquakes were around the fault zone: more than 200 per year.

Many people don’t know what type of natural disaster they might encounter in a new area. If they learn, they can better prepare, said Kevin Borden and Susan Cutter from the Department of Geography of the University of South Carolina

in a 2008 study.

The interactive web site, “

Your State Perils,” tells the most common natural disasters in each state.

“My goal is to get beyond just hearing and understanding the risk, to involving them in what they can do, in case an earthquake does occur,” Evans said.

Have an evacuation plan: Makah tribe, Neah Bay, Wash.

The Makah Tribe lives in the far northwest corner of Washington, right on the coast. That area sits on the edge of the

Cascadia Subduction Zone, a boundary where one tectonic plate slides under another. Such boundaries produce the heaviest earthquakes and tsunamis, like the one that decimated parts of Japan on April 11, 2011.

Every year, the Makah practice a tsunami evacuation. About 600 people took part this year.

[caption id="attachment_19290" align="alignright" width="225"]

Photo courtesy of Andrew Winck, Emergency Management Coordinator for the Makah Tribe[/caption]

When a siren sounds they have about 25 minutes before a tsunami hits, said Andrew Winck, the emergency management coordinator for the Makah Tribe. Preferably, they should drop what they’re doing, grab what they need and follow evacuation routes to one of five assembly areas across the reservation. They could drive, but Winck said damage from a major earthquake might render roads impassable. He estimated it would take 12 to 15 minutes to walk to an assembly area.

That doesn’t leave a lot of time to dawdle. The reservation only has 15 public safety staff, so it’s important that the 1,100-plus tribe members know exactly where to go and what to do. Public safety staff direct traffic, register evacuees at evacuation centers, communicate with an operations center and help with injuries. By practicing their emergency evacuation plans every year, emergency personnel get trained and tribe members better know where to go.

“It gives them confidence the tribe is prepared to take care of them. They’re not just going to go somewhere and be on their own,” Winck said.

Ready.gov recommends every family have an emergency evacuation plan with a meeting place and out-of-area contact information in case family members get separated.

The tribe put its plan to the test in 2011 after the Japanese earthquake. Some small tsunami waves went up the river, Winck said.

“We didn’t really need to evacuate, but we just wanted to just to be on the safe side,” he said.

Attach furniture to the wall: American Red Cross, Costa Mesa, Calif.

The biggest hazard in an earthquake is not falling debris from a building; it’s flying debris from items inside, according to Monica Ruzich, the American Red Cross Preparedness Manager for Orange, Riverside and San Bernardino Counties in California.

“People don’t realize the force with which the earth is shaking can turn regular items into missiles,” she said.

For the Great ShakeOut, the Red Cross setup a booth in an IKEA in Costa Mesa, Calif. to teach shoppers about earthquakes and the hazards of unsecured stuff. IKEA provides free wall mounting kits for its larger furniture.

The store announced the ShakeOut drill over its public address system so Red Cross personnel could demonstrate “

drop, cover, and hold on,” the technique emergency managers recommend for earthquake safety.

Most people who visited the Red Cross booth knew about the ShakeOut and “drop, cover, and hold on,” Ruzich said. Fewer knew about the importance of anchoring their belongings.

It’s not just about earthquakes.

According to data from the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission, unsecured TVs and furniture tip over and kill a child every two weeks on average. Tipped furniture and TVs put 38,000 Americans, two-thirds children under five, in the emergency room every year.

“The impact of a falling TV is like being caught between two NFL linemen colliding at full-speed – 10 times,” said a CPSC release.

TV and furniture wall mounting kits are available for sale online. IKEA has directions for how to mount its furniture

on its web site.

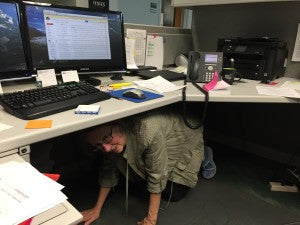

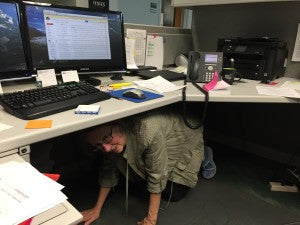

Prepare what you can, when you can: Bartlett High School, Anchorage, Alaska

Bartlett High School often experiences earthquakes. In fact, Prince said she thought there was an earthquake a few days ago, when she saw the walls shaking.

“It was a truck,” she admitted. However, the school felt a real earthquake early this year.

The high school, one of the largest in Alaska, has a strong emergency plan in place. It has areas for two emergency medical sites and a makeshift morgue. Staff members train to participate in medical, search and rescue, student release, and communication teams.

In case of evacuation, staff can grab two rolling coolers that hold information for emergency responders like a building map, teacher schedules, a list of students, and medical needs. They also have tools like keys, a flashlight, and a bullhorn.

Prince’s biggest concern is insufficient supplies. The school doesn’t have a budget for emergency equipment. It has to use fundraisers or donations instead.

“We’ve even advertised on Craigslist,” she said.

Prince said the school needs $8,000 worth of equipment, including hard hats, crowbars, coolers, and first aid supplies.

Preparing for an emergency is daunting for a 1,600-person high school. It can seem almost as daunting for a single family.

The Red Cross has a pamphlet that breaks down a family’s emergency kit into manageable purchases over 21 weeks.

“It just shows people that this is something they can manage to do and does not have to be expensive,” Ruzich said.

Hey, this isn’t that bad: U.S. Geological Survey, San Francisco Bay area

Every year, 600 employees at the USGS’s Menlo Park, Calif. 10-building campus participate in the Great ShakeOut.

[caption id="attachment_19292" align="alignright" width="300"]

Photo courtesy of Susan Garcia from the USGS Earthquake Science Center[/caption]

They perform the “drop, cover, and hold on” drill for a minute then evacuate the buildings to a rally point in a parking lot, said Michael Ramirez, the campus safety officer.

Employees called sweepers walk through buildings, checking offices, labs, restrooms and stairwells and calling out to see if anyone needs help.

This year, for the first time, a few did – sort of.

Planners went around the campus the morning of the drill and asked 16 employees to volunteer to be “injured.” Those employees got a card with an injury and instructions to remain in place. Sweepers had to take the cards and help the “injured” get to a triage area away from the main rally point. This year, the injured were all walking wounded who could be treated with basic first aid.

The incident commander liked the scenario so much he wants to do an earthquake drill semiannually instead of annually and practice more difficult situations, Ramirez said.

“Generally there will be a little bit more scenario on top: broken water lines, a gas main break, this building not habitable,” he said.

It can seem scary or hard to hold family emergency drills. Parents might fear scaring children or giving them nightmares. Yet

studies agree that children who learn about disasters in a safe environment are less afraid during a disaster. They might even want to practice more often.

What did you learn from the Great ShakeOut? Let us know in the comments!

On October 15, Bartlett High School in Anchorage, Alaska, held an earthquake drill for the Great ShakeOut, a global earthquake preparedness day. During the drill, office staff had to try to explain to a parent who didn’t speak English that everyone should drop to the floor, crawl under a solid surface and hang on to that surface. He didn’t understand. They tried to tell him to hold on to the office doorframe. He still didn’t understand: he left then returned. The earthquake drill was only a minute long, and the office staff spent the whole time trying to get him to understand how to participate, said Lisa Prince, an assistant principal over freshmen who coordinated the drill.

Disaster practice like the Great ShakeOut can teach participants what to do and show holes in their preparations. Here are five things ShakeOut participants from all over the country learned.

Know the hazards where you live: University of Missouri, Columbia, Mo.

Almost one in three University of Missouri freshmen in 2011 came from outside the state. That means they may not have heard of the New Madrid fault zone, the most active fault zone east of the Rockies.

Eric Evans, the university’s emergency management coordinator, wants to educate students about it.

With good reason. An earthquake in New Madrid, Mo. on February 11, 1812, caused tremors in Boston and reportedly caused the Mississippi River to flow backwards, according to nationalgeographic.com. Even though the university is about 275 miles away, it’s extremely vulnerable to damage from an earthquake in the New Madrid seismic zone, because of its proximity to the Missouri River, Evans said.

[caption id="attachment_19291" align="alignright" width="300"]

On October 15, Bartlett High School in Anchorage, Alaska, held an earthquake drill for the Great ShakeOut, a global earthquake preparedness day. During the drill, office staff had to try to explain to a parent who didn’t speak English that everyone should drop to the floor, crawl under a solid surface and hang on to that surface. He didn’t understand. They tried to tell him to hold on to the office doorframe. He still didn’t understand: he left then returned. The earthquake drill was only a minute long, and the office staff spent the whole time trying to get him to understand how to participate, said Lisa Prince, an assistant principal over freshmen who coordinated the drill.

Disaster practice like the Great ShakeOut can teach participants what to do and show holes in their preparations. Here are five things ShakeOut participants from all over the country learned.

Know the hazards where you live: University of Missouri, Columbia, Mo.

Almost one in three University of Missouri freshmen in 2011 came from outside the state. That means they may not have heard of the New Madrid fault zone, the most active fault zone east of the Rockies.

Eric Evans, the university’s emergency management coordinator, wants to educate students about it.

With good reason. An earthquake in New Madrid, Mo. on February 11, 1812, caused tremors in Boston and reportedly caused the Mississippi River to flow backwards, according to nationalgeographic.com. Even though the university is about 275 miles away, it’s extremely vulnerable to damage from an earthquake in the New Madrid seismic zone, because of its proximity to the Missouri River, Evans said.

[caption id="attachment_19291" align="alignright" width="300"] Photo courtesy of Eric Evans, Emergency Management Coordinator for the University of Missouri[/caption]

For the university’s Great ShakeOut event, the emergency management office set up maps showing earthquake-prone areas. Students from the Geology Department explained the earthquake risk. Evans said many students were amazed to learn how common earthquakes were around the fault zone: more than 200 per year.

Many people don’t know what type of natural disaster they might encounter in a new area. If they learn, they can better prepare, said Kevin Borden and Susan Cutter from the Department of Geography of the University of South Carolina in a 2008 study.

The interactive web site, “Your State Perils,” tells the most common natural disasters in each state.

“My goal is to get beyond just hearing and understanding the risk, to involving them in what they can do, in case an earthquake does occur,” Evans said.

Have an evacuation plan: Makah tribe, Neah Bay, Wash.

The Makah Tribe lives in the far northwest corner of Washington, right on the coast. That area sits on the edge of the Cascadia Subduction Zone, a boundary where one tectonic plate slides under another. Such boundaries produce the heaviest earthquakes and tsunamis, like the one that decimated parts of Japan on April 11, 2011.

Every year, the Makah practice a tsunami evacuation. About 600 people took part this year.

[caption id="attachment_19290" align="alignright" width="225"]

Photo courtesy of Eric Evans, Emergency Management Coordinator for the University of Missouri[/caption]

For the university’s Great ShakeOut event, the emergency management office set up maps showing earthquake-prone areas. Students from the Geology Department explained the earthquake risk. Evans said many students were amazed to learn how common earthquakes were around the fault zone: more than 200 per year.

Many people don’t know what type of natural disaster they might encounter in a new area. If they learn, they can better prepare, said Kevin Borden and Susan Cutter from the Department of Geography of the University of South Carolina in a 2008 study.

The interactive web site, “Your State Perils,” tells the most common natural disasters in each state.

“My goal is to get beyond just hearing and understanding the risk, to involving them in what they can do, in case an earthquake does occur,” Evans said.

Have an evacuation plan: Makah tribe, Neah Bay, Wash.

The Makah Tribe lives in the far northwest corner of Washington, right on the coast. That area sits on the edge of the Cascadia Subduction Zone, a boundary where one tectonic plate slides under another. Such boundaries produce the heaviest earthquakes and tsunamis, like the one that decimated parts of Japan on April 11, 2011.

Every year, the Makah practice a tsunami evacuation. About 600 people took part this year.

[caption id="attachment_19290" align="alignright" width="225"] Photo courtesy of Andrew Winck, Emergency Management Coordinator for the Makah Tribe[/caption]

When a siren sounds they have about 25 minutes before a tsunami hits, said Andrew Winck, the emergency management coordinator for the Makah Tribe. Preferably, they should drop what they’re doing, grab what they need and follow evacuation routes to one of five assembly areas across the reservation. They could drive, but Winck said damage from a major earthquake might render roads impassable. He estimated it would take 12 to 15 minutes to walk to an assembly area.

That doesn’t leave a lot of time to dawdle. The reservation only has 15 public safety staff, so it’s important that the 1,100-plus tribe members know exactly where to go and what to do. Public safety staff direct traffic, register evacuees at evacuation centers, communicate with an operations center and help with injuries. By practicing their emergency evacuation plans every year, emergency personnel get trained and tribe members better know where to go.

“It gives them confidence the tribe is prepared to take care of them. They’re not just going to go somewhere and be on their own,” Winck said.

Ready.gov recommends every family have an emergency evacuation plan with a meeting place and out-of-area contact information in case family members get separated.

The tribe put its plan to the test in 2011 after the Japanese earthquake. Some small tsunami waves went up the river, Winck said.

“We didn’t really need to evacuate, but we just wanted to just to be on the safe side,” he said.

Attach furniture to the wall: American Red Cross, Costa Mesa, Calif.

The biggest hazard in an earthquake is not falling debris from a building; it’s flying debris from items inside, according to Monica Ruzich, the American Red Cross Preparedness Manager for Orange, Riverside and San Bernardino Counties in California.

“People don’t realize the force with which the earth is shaking can turn regular items into missiles,” she said.

For the Great ShakeOut, the Red Cross setup a booth in an IKEA in Costa Mesa, Calif. to teach shoppers about earthquakes and the hazards of unsecured stuff. IKEA provides free wall mounting kits for its larger furniture.

The store announced the ShakeOut drill over its public address system so Red Cross personnel could demonstrate “drop, cover, and hold on,” the technique emergency managers recommend for earthquake safety.

Most people who visited the Red Cross booth knew about the ShakeOut and “drop, cover, and hold on,” Ruzich said. Fewer knew about the importance of anchoring their belongings.

It’s not just about earthquakes. According to data from the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission, unsecured TVs and furniture tip over and kill a child every two weeks on average. Tipped furniture and TVs put 38,000 Americans, two-thirds children under five, in the emergency room every year.

“The impact of a falling TV is like being caught between two NFL linemen colliding at full-speed – 10 times,” said a CPSC release.

TV and furniture wall mounting kits are available for sale online. IKEA has directions for how to mount its furniture on its web site.

Prepare what you can, when you can: Bartlett High School, Anchorage, Alaska

Bartlett High School often experiences earthquakes. In fact, Prince said she thought there was an earthquake a few days ago, when she saw the walls shaking.

“It was a truck,” she admitted. However, the school felt a real earthquake early this year.

The high school, one of the largest in Alaska, has a strong emergency plan in place. It has areas for two emergency medical sites and a makeshift morgue. Staff members train to participate in medical, search and rescue, student release, and communication teams.

In case of evacuation, staff can grab two rolling coolers that hold information for emergency responders like a building map, teacher schedules, a list of students, and medical needs. They also have tools like keys, a flashlight, and a bullhorn.

Prince’s biggest concern is insufficient supplies. The school doesn’t have a budget for emergency equipment. It has to use fundraisers or donations instead.

“We’ve even advertised on Craigslist,” she said.

Prince said the school needs $8,000 worth of equipment, including hard hats, crowbars, coolers, and first aid supplies.

Preparing for an emergency is daunting for a 1,600-person high school. It can seem almost as daunting for a single family. The Red Cross has a pamphlet that breaks down a family’s emergency kit into manageable purchases over 21 weeks.

“It just shows people that this is something they can manage to do and does not have to be expensive,” Ruzich said.

Hey, this isn’t that bad: U.S. Geological Survey, San Francisco Bay area

Every year, 600 employees at the USGS’s Menlo Park, Calif. 10-building campus participate in the Great ShakeOut.

[caption id="attachment_19292" align="alignright" width="300"]

Photo courtesy of Andrew Winck, Emergency Management Coordinator for the Makah Tribe[/caption]

When a siren sounds they have about 25 minutes before a tsunami hits, said Andrew Winck, the emergency management coordinator for the Makah Tribe. Preferably, they should drop what they’re doing, grab what they need and follow evacuation routes to one of five assembly areas across the reservation. They could drive, but Winck said damage from a major earthquake might render roads impassable. He estimated it would take 12 to 15 minutes to walk to an assembly area.

That doesn’t leave a lot of time to dawdle. The reservation only has 15 public safety staff, so it’s important that the 1,100-plus tribe members know exactly where to go and what to do. Public safety staff direct traffic, register evacuees at evacuation centers, communicate with an operations center and help with injuries. By practicing their emergency evacuation plans every year, emergency personnel get trained and tribe members better know where to go.

“It gives them confidence the tribe is prepared to take care of them. They’re not just going to go somewhere and be on their own,” Winck said.

Ready.gov recommends every family have an emergency evacuation plan with a meeting place and out-of-area contact information in case family members get separated.

The tribe put its plan to the test in 2011 after the Japanese earthquake. Some small tsunami waves went up the river, Winck said.

“We didn’t really need to evacuate, but we just wanted to just to be on the safe side,” he said.

Attach furniture to the wall: American Red Cross, Costa Mesa, Calif.

The biggest hazard in an earthquake is not falling debris from a building; it’s flying debris from items inside, according to Monica Ruzich, the American Red Cross Preparedness Manager for Orange, Riverside and San Bernardino Counties in California.

“People don’t realize the force with which the earth is shaking can turn regular items into missiles,” she said.

For the Great ShakeOut, the Red Cross setup a booth in an IKEA in Costa Mesa, Calif. to teach shoppers about earthquakes and the hazards of unsecured stuff. IKEA provides free wall mounting kits for its larger furniture.

The store announced the ShakeOut drill over its public address system so Red Cross personnel could demonstrate “drop, cover, and hold on,” the technique emergency managers recommend for earthquake safety.

Most people who visited the Red Cross booth knew about the ShakeOut and “drop, cover, and hold on,” Ruzich said. Fewer knew about the importance of anchoring their belongings.

It’s not just about earthquakes. According to data from the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission, unsecured TVs and furniture tip over and kill a child every two weeks on average. Tipped furniture and TVs put 38,000 Americans, two-thirds children under five, in the emergency room every year.

“The impact of a falling TV is like being caught between two NFL linemen colliding at full-speed – 10 times,” said a CPSC release.

TV and furniture wall mounting kits are available for sale online. IKEA has directions for how to mount its furniture on its web site.

Prepare what you can, when you can: Bartlett High School, Anchorage, Alaska

Bartlett High School often experiences earthquakes. In fact, Prince said she thought there was an earthquake a few days ago, when she saw the walls shaking.

“It was a truck,” she admitted. However, the school felt a real earthquake early this year.

The high school, one of the largest in Alaska, has a strong emergency plan in place. It has areas for two emergency medical sites and a makeshift morgue. Staff members train to participate in medical, search and rescue, student release, and communication teams.

In case of evacuation, staff can grab two rolling coolers that hold information for emergency responders like a building map, teacher schedules, a list of students, and medical needs. They also have tools like keys, a flashlight, and a bullhorn.

Prince’s biggest concern is insufficient supplies. The school doesn’t have a budget for emergency equipment. It has to use fundraisers or donations instead.

“We’ve even advertised on Craigslist,” she said.

Prince said the school needs $8,000 worth of equipment, including hard hats, crowbars, coolers, and first aid supplies.

Preparing for an emergency is daunting for a 1,600-person high school. It can seem almost as daunting for a single family. The Red Cross has a pamphlet that breaks down a family’s emergency kit into manageable purchases over 21 weeks.

“It just shows people that this is something they can manage to do and does not have to be expensive,” Ruzich said.

Hey, this isn’t that bad: U.S. Geological Survey, San Francisco Bay area

Every year, 600 employees at the USGS’s Menlo Park, Calif. 10-building campus participate in the Great ShakeOut.

[caption id="attachment_19292" align="alignright" width="300"] Photo courtesy of Susan Garcia from the USGS Earthquake Science Center[/caption]

They perform the “drop, cover, and hold on” drill for a minute then evacuate the buildings to a rally point in a parking lot, said Michael Ramirez, the campus safety officer.

Employees called sweepers walk through buildings, checking offices, labs, restrooms and stairwells and calling out to see if anyone needs help.

This year, for the first time, a few did – sort of.

Planners went around the campus the morning of the drill and asked 16 employees to volunteer to be “injured.” Those employees got a card with an injury and instructions to remain in place. Sweepers had to take the cards and help the “injured” get to a triage area away from the main rally point. This year, the injured were all walking wounded who could be treated with basic first aid.

The incident commander liked the scenario so much he wants to do an earthquake drill semiannually instead of annually and practice more difficult situations, Ramirez said.

“Generally there will be a little bit more scenario on top: broken water lines, a gas main break, this building not habitable,” he said.

It can seem scary or hard to hold family emergency drills. Parents might fear scaring children or giving them nightmares. Yet studies agree that children who learn about disasters in a safe environment are less afraid during a disaster. They might even want to practice more often.

What did you learn from the Great ShakeOut? Let us know in the comments!

Photo courtesy of Susan Garcia from the USGS Earthquake Science Center[/caption]

They perform the “drop, cover, and hold on” drill for a minute then evacuate the buildings to a rally point in a parking lot, said Michael Ramirez, the campus safety officer.

Employees called sweepers walk through buildings, checking offices, labs, restrooms and stairwells and calling out to see if anyone needs help.

This year, for the first time, a few did – sort of.

Planners went around the campus the morning of the drill and asked 16 employees to volunteer to be “injured.” Those employees got a card with an injury and instructions to remain in place. Sweepers had to take the cards and help the “injured” get to a triage area away from the main rally point. This year, the injured were all walking wounded who could be treated with basic first aid.

The incident commander liked the scenario so much he wants to do an earthquake drill semiannually instead of annually and practice more difficult situations, Ramirez said.

“Generally there will be a little bit more scenario on top: broken water lines, a gas main break, this building not habitable,” he said.

It can seem scary or hard to hold family emergency drills. Parents might fear scaring children or giving them nightmares. Yet studies agree that children who learn about disasters in a safe environment are less afraid during a disaster. They might even want to practice more often.

What did you learn from the Great ShakeOut? Let us know in the comments!